Rapid Access: Towards More Accessible International Document Supply

How libraries around the world are building accessibility into the heart of resource sharing

By Kip A. Darling

Abstract:

This article explores how Birmingham City University transformed its document delivery workflow through cross-team collaboration, aligning local service improvement with global accessibility goals. It situates this change within the wider RapidILL community, where libraries across the UK, U.S., Canada, and Australia are adapting to new accessibility regulations and expectations. Drawing on practitioner insights and vendor perspectives, it highlights how technological advances and shared standards are shaping a more inclusive future for international resource sharing.

Curzon Building, home of Curzon Library at Birmingham City University. Photo provided by Kip A. Darling, used with permission.

At Birmingham City University, our Inter-Library Loans (ILL) team once processed RapidILL scans using traditional flatbed scanners scattered across campus. The process was labour-intensive: lining up books against L-shaped corners, flattening them on the scanning plate, capturing one double-page spread at a time, and repeating until finished. Each scan then required manual editing in Adobe Acrobat Pro—rotating pages, cropping blank spaces (and the occasional wristwatch or hairy arm)—followed by a slow page-by-page OCR process with inconsistent results depending on staff skill and patience.

At our satellite libraries, Library Experience and Stock Management staff helped whenever possible, fitting scans around other duties. Although we set performance goals to support accessibility, the reality was that we were working toward that vision one scan at a time rather than systematically.

Restructure as Opportunity

A departmental restructure in late 2024 that initially challenged our staffing levels became a catalyst for change. Library Experience gained new responsibilities and could no longer assist with scanning, while the Stock Management team were redeployed elsewhere. Our ILL team also lost staffing hours, leaving us at a crossroads: either manage with less or take a chance on something better.

Enter our Digitised Services team. They had long provided scans for reading lists and alternative formats for disabled users and were equipped with professional-grade tools. Following a conversation between team coordinators, they offered to fill the gap in our RapidILL lending service provision.

Partnership in Practice

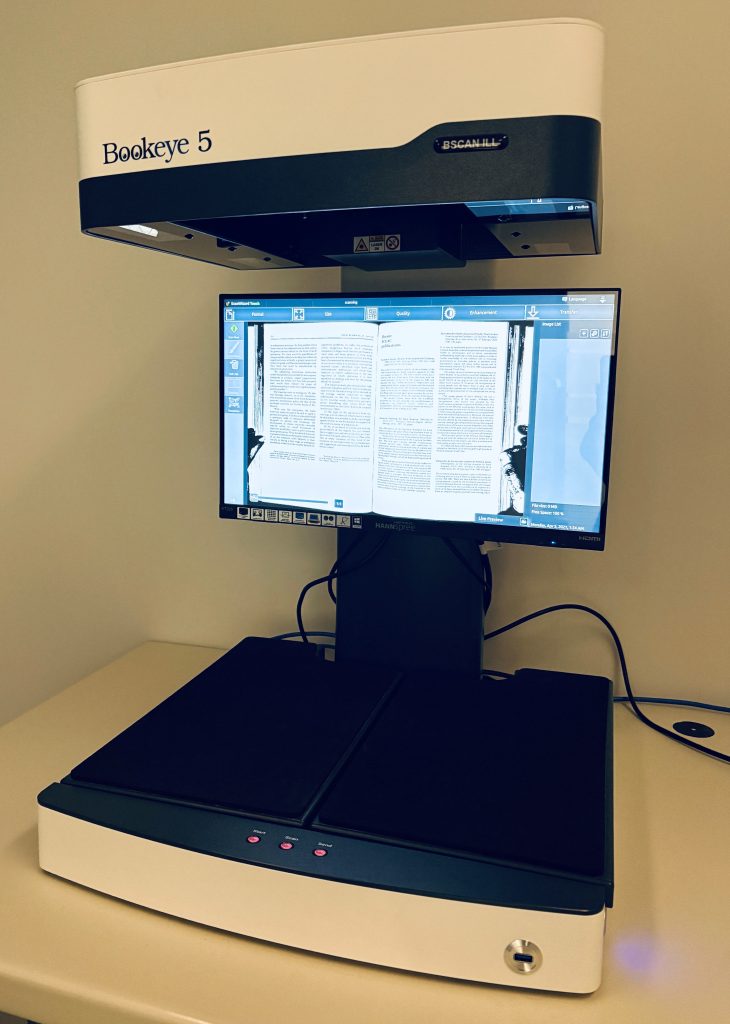

BookEye 5 scanner in use at Queen’s University. Image provided by Nicola Sikkema, used with permission.

Our cross-functional approach soon proved more effective than either team could have achieved alone.

Lee Jones, Coordinator of the Digitised Services team, explains:

“ILL staff handle subject-matter expertise around copyright and patron needs, while we focus on the technical aspects. All requests are logged and tracked, enabling real-time statistics and valuable service insights.

Our equipment includes a Bookeye 5 Archive overhead scanner and ABBYY FineReader software, allowing us to produce high-quality, fully OCR’d documents that meet professional accessibility standards—something difficult and time-consuming to achieve with traditional multifunction devices.”

The Bookeye’s self-adjusting V-shaped cradle preserves book spines while scanning at 120°, and its matching glass plate ensures pages are flat for crisp images ready for OCR. With a 180° glass option for flat items, scan quality up to 600 dpi, and sizing up to A2, the device covers virtually every need.

Once the scan is complete, ABBYY FineReader provides excellent OCR accuracy. Errors are checked and corrected by Digitised Services staff, resulting in accessible PDFs that work reliably with screen readers and other assistive technologies.

“It’s rewarding to know that we’re supporting both our own students and the global RapidILL community,” says Jones. “The consistent quality we deliver helps other libraries serve users with disabilities effectively.”

Meeting International Standards

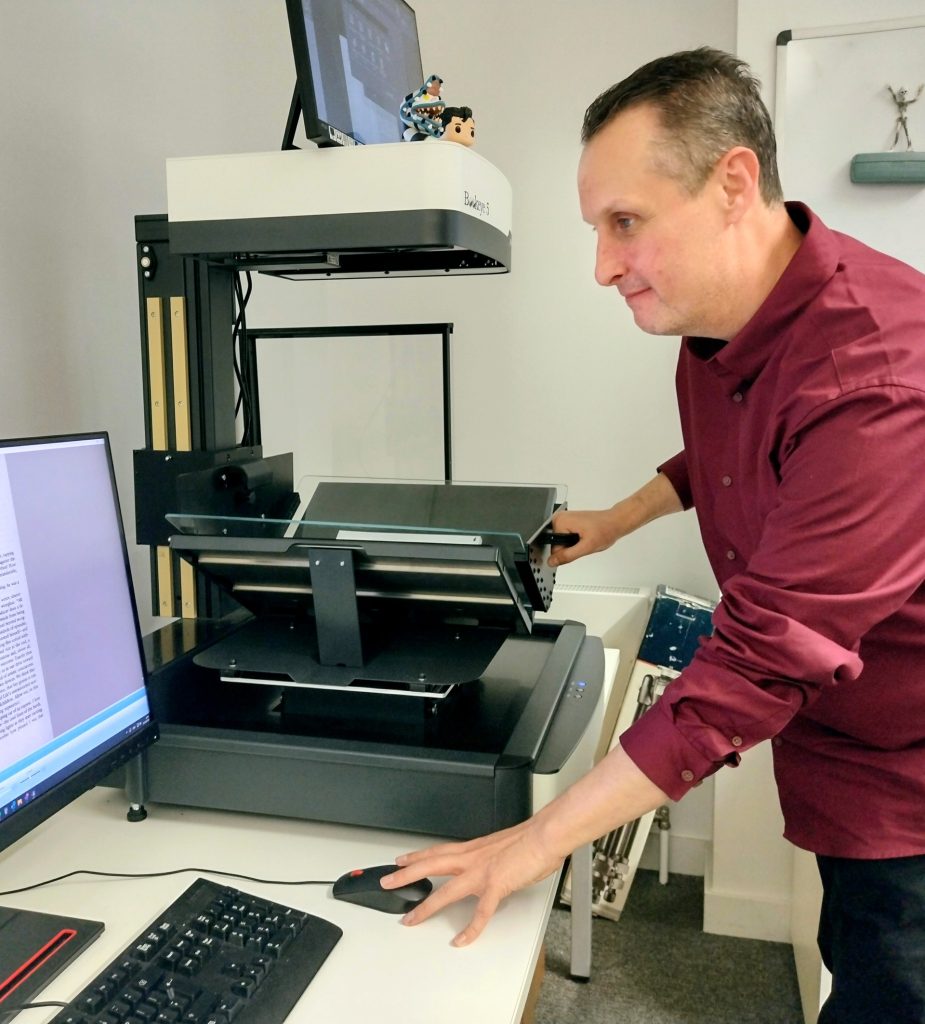

Lee-Jones in the BCU Digitised Services Office. Photo provided by Kip A. Darling, used with permission.

RapidILL now connects over 850 institutions across 36 countries, representing diverse accessibility practices. Australian libraries, for instance, often include title and verso pages in chapter scans—a convention we’ve adopted at BCU. Yet the most significant driver for improved accessibility comes from regulatory change in the United States.

The U.S. Department of Justice’s final rule on Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), published April 24, 2024, requires public academic libraries to ensure their digital services meet WCAG 2.1 AA standards by April 2026. This rule emphasises usability for people with disabilities, not just technical compliance.

In the UK, the Equality Act 2010 and the Public Sector Bodies (Websites and Mobile Applications) Accessibility Regulations 2018 require compliance with WCAG 2.2 AA standards. Although not specific to document delivery, the expectation that accessibility applies across all digital services is increasingly recognised in higher education.

(The authors are library practitioners, not legal professionals. Libraries should consult institutional legal counsel when interpreting accessibility requirements.)

By providing consistently high-quality, accessible scans, libraries contribute to a more inclusive international network of scholarly resources.

U.S. Perspective: Navigating Regulatory Requirements

Courtney Taulbee from the University of Kentucky provides valuable insight into how libraries are interpreting and responding to these regulatory changes:

“The implementation of ADA Title II requirements represents a significant shift for U.S. libraries, particularly those that are government or public institutions. The web content provided from these institutions that fall under the law, like public universities, must meet WCAG 2.1 AA standards by April 2026. This includes content licensed from third-party vendors, such as electronic resources.”

Taulbee notes the collaborative nature of the library community’s response:

“While institutions are determining at a local level how to interpret the law and how it affects their workflow and services, conversations in the ILL community are taking place to determine how best to meet the federal regulations. While not every library may be required to follow this law, the importance of meeting and improving accessibility within our work is widely valued within library services.”

The University of Kentucky’s William T. Young Library. Image credit: Carter Skaggs, University of Kentucky Public Relations, used with permission.

Vendor engagement has become a key strategy:

“Working with our vendors is an essential first step. Our licensed electronic materials need to meet federal guidelines, so ensuring this is built into our vendor contracts allows us to meet one of the accessibility requirements for our users. This also helps with interlibrary loan lending practices, knowing that resources we receive are already in accessible formats.”

For materials that require scanning, automation helps but human review remains essential:

“At the University of Kentucky Libraries, we use scanners that include OCR as part of the process. However, technology does have limitations, so even default automations may require manual intervention from time to time.”

Taulbee’s vision for the future echoes a broader goal:

“Ideally, whether the requested content is born-digital or scanned in-house, the systems and platforms used in ILL services should have accessibility features built in. That way, libraries without the staffing or resources to meet accessibility standards independently can still rely on ILL systems to deliver accessible documents.”

This demonstrates how U.S. regulatory requirements are driving improvements that benefit the entire international community.

“By vendors including these components,” Taulbee concludes, “we not only meet legal obligations but also serve patrons better by providing content that is easier to use. Advocating for this with vendors is important, particularly as ILL services expand and evolve.”

Joseph S. Stauffer Library at Queen’s University, Canada. Image provided by Nicola Sikkema, Queen’s University, used with permission.

Canada’s Vision: An Inclusive, Barrier-Free Solution

Canadian libraries operate within their own accessibility framework but face similar challenges in serving diverse users. Nicola Sikkema from Queen’s University in Kingston describes the national context:

“Canada aims to become an inclusive and barrier-free country, introducing legislation such as the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA) in 2005, which targets accessibility by 2025, and the Accessible Canada Act (ACA) in 2019, a federal law striving for a barrier-free Canada by 2040. How resource sharing digitisation falls within this legislation is ambiguous, but many Ontario universities want to develop shared best practices for accessible digitisation.”

This goal involves significant coordination.

“In 2019, the Ontario Council of University Libraries (OCUL) launched a shared library platform uniting 19 institutions, including Queen’s. Sharing resources brings the added benefit of shared workflows, but creating consistent standards for accessible digitisation remains a challenge due to differences in equipment, software, and staffing.”

At Queen’s University, a local solution emerged:

“We now provide scans that are searchable and readable by screen readers. Last year we purchased a Bookeye scanner and BSCAN ILL software, which removes fingerprints, makes files searchable, and outputs readable documents—all in one program.”

However, monitoring scan quality across automated workflows remains difficult.

“In the early days of RapidILL, we checked all articles for OCR quality before sending them to users,” Sikkema notes. “As staff capacity declined, we shifted to automatic delivery, meaning we could no longer review every file manually.”

Despite these constraints, Canadian libraries are actively testing innovations:

“As part of my work with the Alma Resource Sharing Working Group, we’ve tested sending alternative formats such as EPUB through RapidILL. Although results are promising, we still need vendor improvements to ensure lending libraries can view format-specific request notes.”

Looking ahead, Sikkema sees collaboration as key:

“April 2026 will bring new accessibility rules for our U.S. partners. Although compliance will be challenging, these changes will promote equal access. The majority of our RapidILL requests come from international partners; we hope our own best practices will help support them.”

Australian Innovation: Proactive Accessibility Approaches

Moat with the George Singer Building in the background at La Trobe University, Bundoora, Australia. Image by Phil Lees via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under Creative Commons.

Australian libraries are also leading with proactive solutions. Karen O’Donoghue from La Trobe University Library reflects on the journey:

“The need to make educational materials equally available to all our patrons has been an ongoing aim. Early efforts involved photocopying chapters and posting them to patrons’ homes. Fast forward twenty years, and eBooks and electronic document delivery seemed like the answer—until publisher restrictions on downloading and printing began to limit accessibility.”

Recognising the issue, La Trobe shifted from reactive fixes to proactive service design:

“We saw that staff were responding to accessibility issues only after students received inaccessible files. In 2024, we introduced a new online request form allowing patrons to select their preferred format—large print, Word, audio, and more—with space for additional details. Library staff can now tailor delivery on first supply, and patrons appreciate the improved communication and accessibility.”

This approach demonstrates how understanding user needs upfront transforms accessibility from a corrective task into a preventative service model.

Main Reception at Clarivate Headquarters. Photo by Mictam999 via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under Creative Commons.

The Future: Technical Integration and Automation

Mike Richins, Director of Product Management, Resource Sharing at Clarivate, offers a vendor perspective:

“As the RapidILL, Rapido, and Alma Resource Sharing communities grow worldwide, Clarivate is uniquely positioned to support libraries and their users. Our goal is to provide access to materials not available locally as quickly and efficiently as possible through automation, reduced staff time, and equitable request distribution.”

Richins emphasises accessibility as a core design principle:

“We’re proud to collaborate with a global network of libraries committed to sharing their resources. Accessibility is now central to our conversations with libraries and informs our development roadmap.”

Recent enhancements demonstrate this focus:

“RapidILL now preserves any accessibility features in lender-provided files, ensuring those features are retained across different resource-sharing systems. Borrowers receive files with all accessibility elements intact, regardless of which systems are in use.”

Looking ahead to the ADA compliance deadline, Clarivate is developing new solutions:

“We’re implementing automated OCR processing for files lacking text recognition. With U.S. libraries facing the April 2026 ADA deadline, our goal is to have this in place beforehand, so all users receive accessible documents by default.”

Automation at this level could transform global accessibility, allowing libraries with limited technical capacity to provide consistently inclusive content.

Community Standards and Mutual Support

The strength of the RapidILL community lies in its reciprocity—libraries supporting one another across borders and time zones. When U.S. institutions face stringent accessibility requirements, the quality of scans provided by partners like BCU directly impacts their ability to serve users with disabilities. Similarly, Canadian and Australian initiatives contribute new ideas and workflows that raise standards globally.

This spirit of collaboration extends beyond compliance. By sharing best practices and maintaining high-quality standards, we collectively lift expectations across the network. Libraries in regions without strict legal obligations often exceed baseline requirements because they recognise their global role. This approach was exemplified in a recent ELUNA survey gathering best practices and case studies to drive community-powered training and advocacy for change.

Looking Forward

As we continue refining our processes, we remain mindful of our responsibility to the broader RapidILL community. The regulatory landscape continues to evolve, and user expectations for accessible content are rising too. Libraries that invest in accessible document delivery today position themselves as leaders in inclusive resource sharing.

Our journey from manual scanning to professional digitisation represents more than operational improvement—it reflects a commitment to ensuring that geographical location or institutional resources never determine access to scholarly materials. In an increasingly connected world, accessibility is not just a local concern; it is a global responsibility.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Lee Jones (Birmingham City University, UK), Karen O’Donoghue (La Trobe University, Australia), Courtney Taulbee (University of Kentucky, USA), Nicola Sikkema (Queen’s University, Canada), and Mike Richins (Clarivate) for their generous contributions and insights, which illustrate the international and industry dimensions of accessible document delivery.

Additional resource:

Orbis Cascade Alliance Accessibility Toolkit: https://www.orbiscascade.org/programs/dux/documentation/accessibility-toolkit/